Throughout his directing career, Ryusuke Hamaguchi always has an interest in grasping the murk between pretension and authentic human emotions. In Asako I&II, he asks the same actor to portray behaviourally opposite love interests to muffle the relationship between unattainable love and mundane love. In Wheel of Fortune of Fantasy, human connections are found through three individual stories of playful mind games. In Drive My Car, he builds the dramaturgical triad of work, art, and life to see where catharsis would fit in. All three films are interrogative and quasi-preternatural which amounts to the feeling of dissecting your own dreams. Evil Does Not Exist to me is about perception, the way different kinds of people see the world. It is a far more radical output for Hamaguchi, both in terms of its subject matter and the way he employs his style onto an uncharted, surrealistic canvas. If Hamaguchi’s previous works are lucid dreams, then Evil Does Not Exist is a dread-infused nightmare that will shatter whatever previous notion you have about his films or even the world we live in at large.

The film’s impetus revolves around its composer, Eiko Ishibashi (the same composer as Drive My Car), requesting Hamaguchi to make a film that accompanies her new album. Unsure of his approach, Hamaguchi decides to research Ishibashi’s musical process, and through that, he learns nature is a critical inspiration for Ishibashi and decides on the film’s setting, a rural village named Mizubuki that is close to where his composer actually works. The score is at times reminiscent of Max Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight, at times experimental horror beats unrecognizable from the sound design. Its malleable form compliments the film’s elemental imagery. The film’s opening is a gliding shot of the camera gazing up at the sky filled with overhead canopies. Companied by Ishibashi’s melancholic violin, the atmosphere becomes eerie. The unsettling feeling stems from us viewers questioning what perspective we are looking at this shot from. It’s starting to feel as if the trees are trying to whisper something to us. In most scenes that contain music, the score always abruptly cuts off. During an interview at NYFF, Hamaguchi mentioned this is a response from him to preserve the beauty of the music while still creating a distance between the score and the images themselves. This devoid of emotional manipulation is what separates the film from its more traditional counterparts.

In the context of Hamaguchi’s oeuvre, the most disparate element of this film is its setting. So far in his career, Hamaguchi has been a city man. His characters usually live in a metropolis like Tokyo, which is populated by city lights, subways, and high-rise buildings. With Evil Does Not Exist, he chooses to tell a story 2 hours outside of Tokyo. Mizubuki is a peaceful village with only a handful of inhabitants. Its tranquil sceneries attract a Tokyo-based model agency to come in and propose the development plan for a glamping site. The term “glamping” stands for glamorous camping. It is designed for city folks who want to immerse themselves in raw nature without making any real effort. This concept itself, the idea of authenticity versus embellishment, is crucial to the film’s central conflict. There is a trite version of this film – a didactic moralist tale where its making is analogous to the film’s critique – a big city crew trots into a small town, enforces a cliched story of right and wrong, and decorates the place with veneers of travelogue vistas. Luckily, Evil Does Not Exist is spared of this hypothesis. It is a film that is as perceptive as it is ambiguous as it is atmospheric.

In the beginning, we are introduced to Takumi, a middle-aged, self-proclaimed jack-of-all-trade handyman. He has an 8-year-old daughter who often wanders off into the woods for her own quests. The first act of the film follows him executing his daily routine as he saws and chops a tree trunk into firewood, scoops up water from the creek for the local ramen restaurant, and picks up his daughter from daycare (although he always misses her when he gets there). Hamaguchi films all of Takumi’s actions with rigid, ingenuous neutrality. We never intrude on any of his actions, the shots never break as we observe him perform these tasks in real time. The blockings have assimilated the viewers into the presence of trees, phragmites, and the frozen river. We are also treated with sensorial pleasures from the thump of a piece of wood falling on the ground, footsteps treading on snow and fallen leaves, and the drizzling water running through the creek. This modest, documentarian quality removes the glamour and finds peace in mundane work. We get an accurate look at what lives are like when you live in a rural village.

The film never explains Takumi’s inner emotions. For the majority of the film, we observe him in medium and long shots in harmony with his natural surroundings. We learn he is a widower from a photo on his living room table but never does he strike a monologue about his wife or speak much at all. When he does open his mouth, his voice has a chilling stream of clarity that sounds identical to the water flowing down a creek. He is revered by other villagers for his knowledge of every species of bird and plant in the village. There’s a sense that he has been living on this land for so long that he is basically blending in with the landscapes. Every one of his actions feels determined yet unassuming. Hitoshi Omika gives a rare performance that is hard to pinpoint yet extremely captivating. This captivation emphasizes the film’s unique magic – the ability to provide new perspectives, narratively and formally.

As a great director does, Hamaguchi would often disorient our perception by breaking his formal documentarian approach. He is discontent with us simply observing. We are subjected to perspectives of different objects along Takumi’s daily routine. When Takumi introduces the ramen restaurant owner to a kind of wasabi leaf, the scene is shot from the perspective of the plant. When he drives away from the daycare to find his daughter, we watch the departure from the viewpoint of the van’s rear end. Later in the film, we see a shot from the perspective of a rotting deer corpse. These shots submerge the audience deeper into this world as we become a part of nature itself. They also provide a chilling semi-fourth-wall-breaking effect as the characters are looking right into the camera, and subsequently into us. We often hear in reviews that locations can be characters themselves. Here, Hamaguchi accomplishes that through pure formal talent. He introduces everything in this place collectively as a dormant giant and hints there is so much we don’t see beneath the surface.

Evil Does Not Exist expands its perspective as it progresses. In what is arguably the film’s most compelling scene, two corporate representatives host a council meeting and answer the villagers’ concerns. Hamaguchi moves his sharp, formal elegance indoors as he authentically frames the procedural. His talent for capturing real human faces shines the brightest here. We witness Takumi and a few other villagers sincerely raising their concerns. Their faces and desperate eyes relent a sense of urgency and authenticity in dichotomy with the brazen, fake smiley face and diplomatic posturing of the two representatives. The naturalistic style shows a sign of respect to the individuals pleading their case and a form of confidence from Hamaguchi to direct a gripping scene without extra artifice. A major concern lies in the creation of a septic tank that will release human waste into lower streams that the locals feed on – the locals will have literal shit in their daily water. The accrual of their agony, hopelessness, and pleads blends the grand social injustice and dumbfounded ridiculousness of corporal greed with the precarious personal. Watching the defeated faces of the two presenters is marginally rewarding and more dreadful to realize their futility.

The most surprising narrative twist in Evil Does Not Exist is the perspective shift onto the two corporate representatives. This change deftly recontextualizes the previous council meeting. Through Hamaguchi’s penchant for long vehicular conversations, the two are humanized as we learn about their personalities on a drive back to Mizubuki. Here lies the greatest strength of Evil Does Not Exist – despite all of its unorthodox elements, it never loses the inherent logic of a capitalist society. Our malevolence towards the two slowly erodes as the film astutely points out the obvious – the two representatives are just little vulnerable pieces within the rampant capitalist system. They both contain hubris and ignorance, but what human doesn’t? The two return to Mizubuki in the third act, and what follows is a dreamlike journey they take with Takumi, which I will not spoil. All I can say is to pay attention to how the scenes are structured compared to the first act. For a film with “evil” in its title, it’s more unnerving and frustrating that the evil cannot be easily identified.

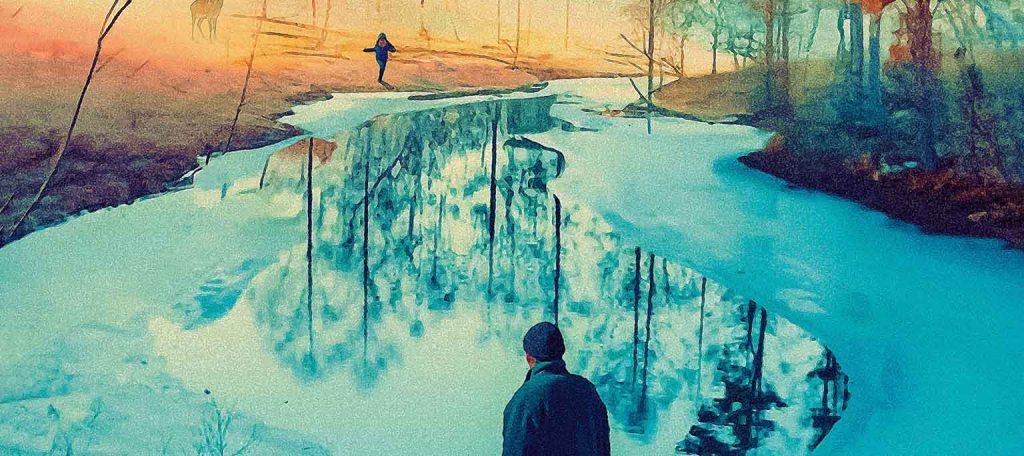

The naturalistic setting allows Hamaguchi to create some of the most striking imagery in his career, making the film a masterful mood piece. The landscapes are not ornamental backdrops, they take the front stage to reveal something more personal and malicious. He captures the unnerve within the limpid, frozen lake, smoke rushing out of the chimney in front of the magic hour sunset. A pile of smoking cow feces is transformed into one of the most memorable frames you will find in a film this year. A single drip of blood creates more intense fear than most horror films. We hear sporadic gunshots from unknown deer hunters afar, are these red herrings or harbingers of imminent danger? The inner logic of the film begins to dispatch from the common sense as the area gets physically mistier. Evil Does Not Exist is filled with iconoclast imageries that make you question your own place in this world and whether you understand how the world works at all.

Following the film’s release, the most discussed and debated-over element is its ending. A lot of people are baffled by the events, and some even call it senseless. It’s understandable to be confused; most of the characters in the film are also struggling with their place in the world, and the film itself is covered by mist by the end. Having only seen the film once, I find the ending abstract but intuitive. It is one of the most assured endings I’ve seen from a new release this year. Without spoilers, it’s where the natural and the proverbial join paths. Throughout the film, there is a knowledge gap between the village folks and the city dwellers. The village elders and Takumi respect nature, they believe people upstream need to take care of the people downstream. The people from the glamping company believe they need to begin construction as soon as possible to stay ahead of the competition and keep the government subsidies. It is this gap between the laws of the natural world and the laws of capitalism that creates an imbalance, but nature is all about keeping its balance in whatever ways it can. Evil Does Not Exist ultimately strikes as a hypnotic tale of activism and justifies it not with morals but with self-defence against animosity. It’s a quasi-meta-physical representation of how human instinct works, which Hamaguchi provokes with impeccable and raw formal control.

Leave a comment