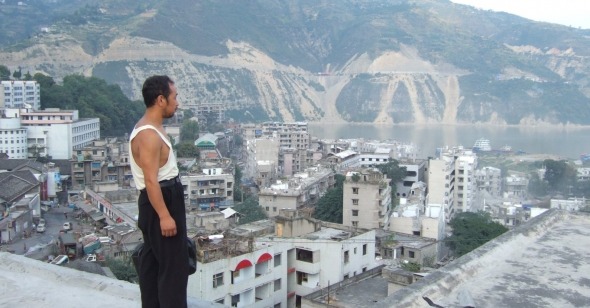

Three thousand years of history desecrated in 2 years in the name of progress. A city gradually turns itself into ruins and eventually disappears underwater. Jia Zhangke’s 2006 Venice Golden Lion Winning Still Life is a primal representation of what Andre Bazin described as the Mummy Complex – a story of longing and seeking the long gone through an artform that preserves – for Fengjie which will officially be underwater by May 1st, 2006. Jia’s films have always been dense in their cultural context, and their main characters are delineated in detail by how their surroundings confine and define their actions. This is more evident and successful in his 2002 Unknown Pleasures, where he creates an invisible circle around his two aimless protagonists that plays an extremely sad joke. A tragic feeling arises when you realize filming is Jia’s way of savouring recognizable moments of his hometown that are washed over by political and economic currents. In Still Life, however, he assumes his perspective through the journey of two outsiders. In two almost completely separate stories, both protagonists are from Shanxi and look for their estranged spouses, the two never meet, and their paths only cross in elliptical terms.

The ambivalence towards progress is prevalent throughout Jia’s oeuvre and becomes evident in the opening sequence. In the opening, long, pensive shots sweep across the interior of a ship travelling on the Yangtze River. Passengers playing cards, laughing, cavorting, and arm wrestling, with the camera focus fading in and out as if the tears of the masses are blurring the lens. We later find Han Sanming standing near the boat’s edge, looking far into the mountains. What is he ruminating on? The foregone or the uncertain future, or both? The question is soon answered. Sanming is looking for his wife, who ran away with his infant daughter from his hometown, Shanxi, 16 years ago. To his surprise, the address he was given has already been inundated by water, and there is barely a signal of life there. Fengjie is now populated by local gangs picking up what the riches left behind, stubborn old people still unready to move on, and businessmen trying to get first dips at the big bucks of reconstructing the town. The husband of Shen Hong is an exemplary opportunist. Having left Shanxi two years ago, he has successfully found his wealth in Fengjie, leaving his wife stranded at home with a 7-digit phone number that no longer works. With such unbearable longings, Shen Hong travels to Fengjie to seek some sort of reunion or resolution.

This character is slightly different from Jia’s muse, Zhao Tao, who usually assimilates into the local environment of the shooting location. Differs from Han Sanming, who easily finds companionships with local gangsters and construction workers, Zhao’s Shen Hong always stands out whenever she takes the screen. Her straight posture gives off a sense of righteousness that amplifies the exasperation of her need to find her husband and life back. This may also be caused by her being a woman. Jia has an astute eye for gender observation. In a town that’s moving backward in civilization, the roles of women have reverted back to prostitutes and stay-at-home cooks. The only women who can avert such status are outsiders like Shen or a businesswoman from Xiameng, who we only see on posters. Perhaps that’s why Shen looks so conspicuous everywhere she goes.

In additon to the two segmented stories, Still Life is broken downs into chapters – cigarette (烟), alcohol (酒), tea (茶) – common items in social exchanges. The social observation is alertly captured through Han Sanming gifting alcohol and lighting cigarettes for people he needs a favour from. Jia chooses not to be similar social exchanges in the business world that controls the bigger picture of the town, but it is easy to imagine these callous and dire exchanges behind-the-scenes that decided the fate of millions, especially in one particular scene where a group of businessmen mingled in an open-air bar at night where one of them shows off his newest achievement to the rest, a bridge that lights up so bright at night it makes the rest of the town so much darker. In Jia’s films, the implications are usually scarier than what’s shown.

The role of locations, sound, and the sense of atmosphere are instrumental in Still Life‘s overall aesthetic. The locals are characterized by their surroundings, and they contain myriads of emotions contained within the ruins of Fengjie. Conspicuous red markings are painted onto the background walls that signal how the city you see now will be sunken shortly, serving as a glacial ticking time tomb and a dark joke. A majority of scenes are plagued by background noises of large construction pieces of machinery banging, drilling, and excavating buildings – they serve as loud notifications to the locals that they are not welcome anymore and move out of the way as fast as possible – it’s astounding how would anyone get any sleep living there. The majority of the places look so out of shape that it resembles a dystopian world, a la Mad Max, but the film’s surface looks every bit as authenticated as it can be. The idea of documenting a place before it’s too late coheres with the elegiac beauty Jia and cinematographer Yu Lik-wai try to fill within every scene. The film has its eyes on the fragmented buildings, structures, large industrial plants, and abandoned buildings with white paintings marking the word “拆,” meaning demolished. The dramatic irony in this pictorial visual is highlighted by the conspicuously glossy new infrastructure that Shen Hong visits to find her husband. The background is always in silent conversation with people in the frame. It is no coincidence that the most dramatic conversation regarding a farewell is set in front of the Three Gorges Dam, which is the genesis of everything.

The cultural context behind and the stories within Still Life are both about holding onto something slipping away or already having. This “something” is expressed in ambiguous and intangible terms through a dissonance between the familiarity of the stories and the authenticity of the setting. Both stories feel similar to the Heart of Darkness archetype, where a character ventures into an unknown location and seeks a missing person. Here, the stories are clad with a similar aimlessness as Jia’s previous Unknown Pleasures. As the characters are actively seeking their partners, the film is granted a travelogue quality and more dramatic elements than any of his previous works. With a visible dramatic arc, the film can feel more inert than desired. Han Songming and Shen Hong actively feel out of place. Not only do Han Sanming and Zhao Tao speak Mandarin with very to no accent, different from the local dialects (there are even scenes that remark this different), but the camera often frames them in the center posing aimlessly, in contrast with locals in the background occupied by their daily ordeal. The heightened drama of the stories risks breaking the verisimilitude that serves as one of the primal virtues of Jia’s cinema, but the transient vacuum created by the dissonance buttresses the idea of weariness that never escapes the frame. The rise of water level is a disaster invisible to ostensible perception – you are aware of the impending doom, but you can’t physically see it yet – similar to the locals who know they will soon be displaced but carry on their work anyway because that’s the only way to survive. In this term, the constantly panning camera sweeps alongside the movement of Sanming and Shen Hong across the ruins might be a way of silent yearning that screams for help to break the semblance of normalcy.

Still Life also continues Jia’s venture into digital experimentation. The smooth digital imageries present Jia with opportunities to manipulate the gorgeous landscapes, which he utilizes in a very playful and sporadic manner. Through heightened reality, he emphasizes the film’s inherent quality of spectatorship. Bizarre sequences clad with digital effects appear during the film. He invites supernatural and technological prophecies that link character arcs and doubles down on his commentary on progress. Nonetheless, the haphazard appearance of these effects is always in service of the observations and never appears garish; sometimes, they just sit in the background, waiting for the audience to look closer. In other words, Jia never loses the grasp of his form.

His rigorous formal control is a way of honestly documenting the locals who are inadvertently uprooted by their country’s prosperity. Jia and his crew do not patronize or speak in their place. The purpose, to me, was to mark these moments as proof that they actually once existed. The narrative may come at odds with the realism, but Jia provides patience and respect to the working class. The film is quietly optimistic amidst all its depressing documentation. It believes that people will invariably find a way to live with themselves in this world. The impermanence across the succession of political powers and ideals, in how the working class is treated and how they manage to survive at all times, is silently conveyed, and it’s all the more powerful. When they say farewell to each other, he does not emphasize the moment by cutting to a close-up, they simply move on. The characters’ resilience is ultimately attributed to their stillness in one of the final shots of the film, a glacially panning shot marked by the still of construction workers together in a room eating, drinking, and prospecting about the future. It’s a sequence centred on community, hope, and tragic fate. In stillness, we observe life, no matter how meagre they seem to be.

Leave a comment