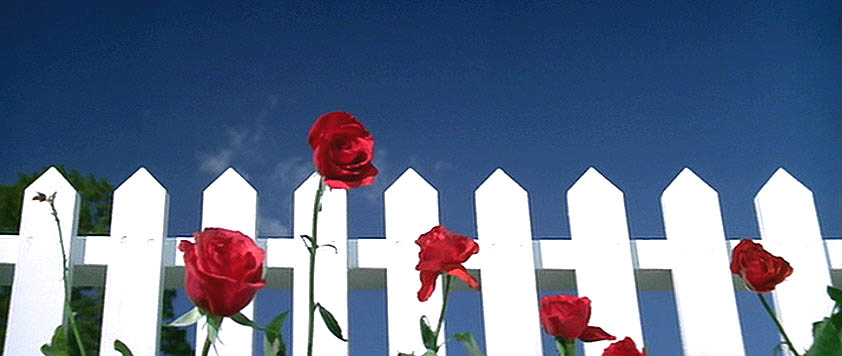

Looking back at David Lynch’s three movie outputs from the 80s, Blue Velvet can easily be viewed as a standalone representation of his oeuvre. The traditional narrative of The Elephant Man does not sufficiently cover Lynch’s sensibility in the eyes of his fans; most people are inclined to forget about the peculiar 1984 adaptation of Dune; therefore, Blue Velvet‘s neo-noir story with a touch of dreamlike abstraction makes it an official “Lynchian” film. The movie opens with a thick blue velvet curtain wobbling as the film credits roll over it. The following is a fade into a clear blue sky from which the camera pans down to a row of bright red roses in front of a freshly painted white picket fence, symbolizing the peace and quietude of the suburban Americana.

The opening montage maintains this benevolent and innocuous quality across a series of thematically related crossfades between slow motions of firefighters waving at the camera as a firetruck drives down the street and children crossing the street after school assisted by an avuncular crossing guard. You can say the actual actions being photographed in them matter less than the collective, symbolic goodness they are associated with. This montage inculcates an idealistic viewpoint that suddenly gets intruded when the lead, Jeffery Beaumont’s father falls upon his front lawn in abysmal pain as the film associates this pain with a granular close-up of the maggots lurking beneath the Beaumont’s lawn.

The opening of the film is a harbinger of the main dichotomy Lynch is trying to explore in Blue Velvet, the battle being good and evil, darkness and light. Such dichotomy is also evident between what the characters in the film are watching and their living environment. Before Jeffery’s father falls to the ground, the film shows an image of a TV, within it a close-up of a gun; before Jeffery departs his home to meet with Detective Williams, the film shows another image of TV which features a staircase. Both images contain genre elements of the 50s noir, which the plot of the film is influenced by. Through these associative moments, Lynch projects darkness into a place where it is only observed as spectacles on a TV from the comfort of one’s own sofa.

Although categorized as a noir, Lynch’s approach in Blue Velvet is heavily different from the genre norm. Most classic noirs are known for their contrivances and dense plot twists. Conversely, Jeffrey’s detective journey in Blue Velvet is mostly passive. When he takes action – such as when he stakes outside of a building to take pictures of Frank and his accomplices – these events are presented in recollections that feel secondary to a heightened drama occurring on another level of the film. Jeffery’s passiveness carries a certain purpose to itself. The role of Maclachlan is different from those of Humphrey Bogart, Glenn Ford, or Jimmy Stewart. Jeffery is more subdued and his presence is closer to a blank canvas. He might be overly curious to the point of creepiness but he is certainly not evil. The affliction of pain and evil transposed through his pedestrian perception is where the film’s main dramatic power stems from.

The best noirs are about necrophiliacs. Hitchcock’s Vertigo and Preminger’s Laura are both about one’s attraction to an imagined, self-manifested version of a victim; Rear Window constructs an entire film out of morbid curiosity from an apartment. Through the creeks of the closet, Jeffery’s peek mirrors the audience’s desires for answers or anything fascinating, even if the answers are most likely to be undesirable. Sandy remarks, “I don’t know if you are a detective or a pervert”, what the film shows after Jeffery enters the closet would lean towards the latter. Notably, the first interaction we see between Frank and Dorothy is not solely attributed to Jeffery’s perspective from within the closet; the sequence contains several axial cuts that get the audience closer to the action.

The most fascinating input from Lynch towards the overall noir framework is Dorothy’s apartment. To the Lynch/Oz obsessive theorists out there, the name Dorothy should ring a very loud bell. As I have not delved into any theory regarding this area, I will just leave it here. However, the moment Jeffery enters Dorothy’s apartment pretending to be the bug man feels like a transgression into a different realm, an abstract understanding of spaces that dominates the best of Lynch’s cinema. The crimson carpet battling with the kitchen tiles draws out every single feature in this space as an isolated object. As prevalent as the use of frame within a frame, the designation of colours within a room makes everything feel like objects stranded within a 3D plane. This leads to the character’s actions being more conspicuous. With the widescreen cinematography of Frederick Elmes, the apartment turns into a stage where actions erupt and heighten. This is the best and most sensible avant-garde touch Lynch can provide the film with.

Because much of the film is dominated by many symbols, their usage in the movie sometimes becomes overbearing and seems like a betrayal of its origins. The foremost example is the usage of Laura Dern’s character. In her initial appearance, she is introduced with a soft offscreen voice, from which emerges her purposefully overlit face from the dark neighbourhood street. Later in the movie, she delivers a story with grand symbols regarding robins and how their reappearance will bring light back to the world again. Gestures such as these render the characters, their faces and gestures into generalized symbols. One of the most alluring features of the great noirs of the past is they are centred around human actions and passions clearly detected by the close-ups on the actors’ faces.

Luckily, Lynch has always been great with his actors the trouble with symbolism is not enough to hijack the performances by Dennis Hopper and Isabella Rossellini. In the most blatant sense, Hopper’s Frank Booth represents all the evil in the world. Jefferey even remarks on that very fact, “Why do people like Frank exist?” His presence and mannerisms are conspicuously aggressive but their origins remain an interesting mystery to unveil. His physical abuse of Dorothy and his particular attraction to her breast contains a childish grump that insinuates something primal and innate as if he is born evil and integral to nature as anything benign. Rossellini provides an unresolvable edge to Dorothy. Her initial reaction towards Jeffery’s intrusion into her apartment refracts Frank’s aggression towards her into a form of yearning for any form of physical affection. Her renditions of the titular song under the mysterious blue spotlights are luring. Unlike Frank, Dorothy can settle into moments of calmness and then accentuate into inexplicable chaos and pain. Perhaps she is the film’s greatest mystery to solve.

I believe Blue Velvet is not close to Lynch’s finest works, especially his magnum opus Mulholland Drive, a film I hope I will go into at length in the future. A surrealist element that is repeated and much more accomplished in Mulholland Drive surrounds the artifice of a pretended singer. Without Spoiling Mulholland Drive, the use of that artifice companies a significant turn in that film’s construction that dances perfectly with the emotional punch of a rug pull. In Blue Velvet, this act is carried out beautifully by Dean Stockwell’s Ben with the song “In Dreams” by Roy Orbison. Like the rest of the movie, this choice is an interesting choice that does not play well with the film’s overall coherence. Like a dull knife, the danger pertains to the looks of it. Because it plays close to a noir thriller, Blue Velvet serves as a great gateway into Lynch’s style, but there are better works that lie before and behind him.

Leave a comment