Shōhei Imamura’s The Eel won the Palme d’Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival in a tie with Abbas Kiarostami’s legendary Taste of Cherry. Since then, there have been chatters that questioned this tie due to the gap in quality between the two films. The latter is now unanimously considered a cinephile classic with a stamp of approval from The Criterion Collection. In the 2022 Sight and Sound poll of the greatest films of all time, the director’s list has it at 93rd and the critics’ at 243rd; The Eel was nowhere to be found. However, I think this uneven critical reception is a result of distribution instead of the qualities of the films themselves. Case in point, I saw Taste of Cherry at the age of 16 on the Criterion Channel and only managed to see The Eel for the first time after Radiance Films’ recent Blu-ray release. While I think Taste of Cherry is a masterwork, The Eel is nonetheless excellent and should not be ignored.

I should start by stating my only unfavourable opinion on the film: I wish that during any stage of production, someone in Imamura’s crew would ask him to go a little bit easier on the eel analogies. Granted, he’s an old revered master and nobody would like or be able to be the one to inhibit him from any artistic ventures. The issue I have is that the eel solely functions as a metaphorical device instead of a narrative one; the story and the actors wonderfully convey the film’s ideas of communal acceptance and second chances without the eel. The titular creature turns into more of an afterthought towards the end.

I enjoy everything else about the film. This is the first I’ve seen from Imamura, so I can’t speak on how this late work plays into the rest of his filmography. It’s a synthesis of many genre ideas: a prologue that is reminiscent of Cure, where domestic order is imbalanced by a mysterious party, which is The Eel’s case is a letter from an absent female voice; later the film takes on tinges of Hitcockian intrigue during the discovery of a body, Yakuza screwball, Japanese monster, and sprinkles of Ozu. This may sound messy, but this is where Imamura’s perspective and command of the space come to preserve the film from tonal whiplashes. He often employs wide shots that absorb moments of over-the-top actions and strategically uses abrupt cuts and cross-fades to establish a dreamlike dimension that challenges the bucolic setting and peaceful present of Takuro and Keiko, who are both grappling with unsettling pasts.

The Hitchcockian aspects of the film can also be attributed to the coincidental connection between the wife Takuro murders and Keiko. The film makes explicit that Keiko is the same age as Takuro’s wife when she died. The twofold interpretation is, first, this is an elusive offer for Takuro to continue on his domestic life with a fresh start and second, a commentary on how prison only manages to waste Takuro’s natural life and halt any spiritual developments or reconciliations he may have. This is shown by how Takuro’s lack of conversation skills and stringent, militaristic behaviour are when he is first released. Visually, mirroring the physical gestures of Keiko and Takuro’s wife is a test for Takuro to see them as separate individuals and accept reality as it is. The most evident is the lunchbox as a recurring, dramatized object that suggests a secure domestic order and whether Takuro chooses to partake in it once more. There is also a Peeping Tom sequence that visually echoes Takuro’s sexual insecurity; perhaps the best placed eel analogy.

The futility of prison and the parole system is dramatically shown through Takuro’s former inmate Dojima, who, despite reciting a mantra every day, is ironically the one person who does not accept Takuro. This is one of the many character ironies Immanura places throughout the film – the UFO-obsessed village dimwit is the most perceptive to see Takuro only talks to his eel because he is unable to talk to human, the initial image of Keiko as a suicidal woman is offset by her positivity and professional businesswoman image, the many village inhabitants who friendly treats Takuro no matter what.

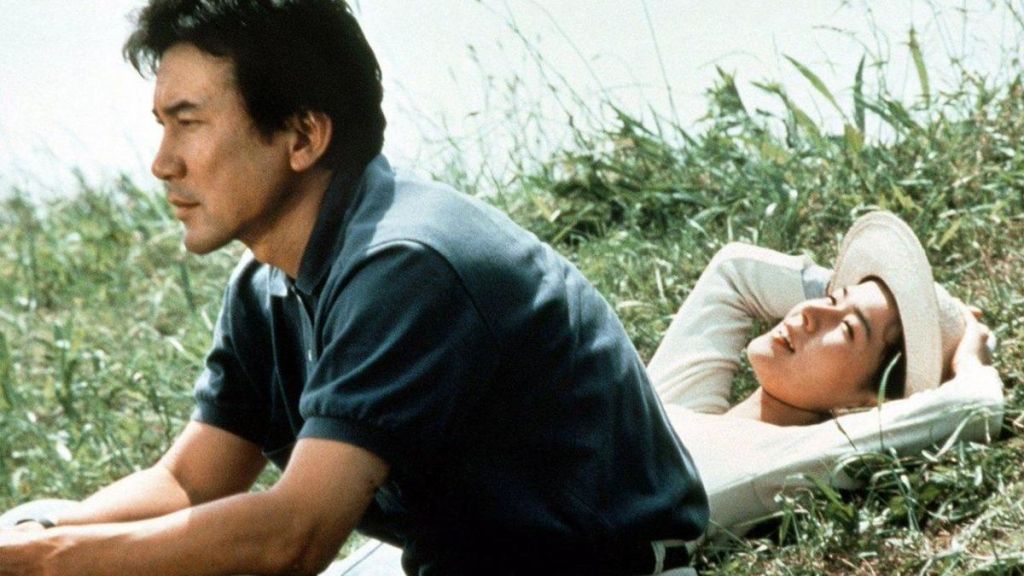

The exemplary scene that showcases Imamura’s brilliant, humanistic touch is the interaction between Takuro and Takada on a boat during sunset. Takuro is afraid the village’s people would reject and expel him if they discover he is a wife murderer on parole. His guilt triggers hallucinations and nightmares, and his unwillingness to move on turns him taciturn. However, after learning about Takuro’s past, Takada simply offers him a drink and starts talking about eels. The entire scene is shot in a single, long shot without any close-ups or sentimental music to emphasize this humanistic moment; yet, the human gestures and the painterly phragmites gently stroked by the wind convey a simple yet powerful wisdom that is deeply moving, even when captured from afar. The camera slowly follows the lateral movement of the boat, as if nothing is major in the context of the earth and the water. In this sense, The Eel does carry a similar idea to The Taste of Cherry: the testament of an individual against a vast landscape. What will happen next? Will he return? Who knows? We can only hope, but at least he was there.

Leave a comment