The Lady from Shanghai

Welles’s demiurgical fable. See how he films the interiors of the courtroom: from an extreme wide angle looking down at everyone; he positions himself above the situation at hand, which contains ridiculous moments such as Mr. Bannister cross-examining himself. This pride continues until it finds Rita Hayworth at the stand, where Welles then films everyone using more tender close-ups; the style serves as a guiding hand towards Welles/Mike’s only point of vulnerability. The mirror sequence in the end is one of the greatest late-film adrenaline boosts – identities and projected presence become shattered. No matter how many times a physical body is reflected, its image remains the same.

Séance

Kurosawa originally made this for TV, but it is deeply cinematic and contains his usual scrupulous dissection of spaces and obscuring iconographies to achieve a peculiar sense of malaise and detachment. More than his other works, Séance is concerned a lot about cursed fate and fated curse, and makes them inherent within the plot mechanism. The wife, Junko, is born with psychic abilities that allow her to see ghosts, sometimes involuntarily. But her natural gift does not buttress her value within the society; neither her domestic life nor her work life benefits from this gift. So the film gradually shifts into a cosmically tragic and subtly funny tale about a very peculiar case of midlife crisis; the act of finding use one’s god-given abilities so that they can transcend the everyday mundanity;

The husband, played by Koji Yakusho, is a professional sound engineer who records sound for various media purposes. This acknowledgement that the sounds within our world are separable from its images is congruous with the way Kurosawa makes the quotidian life and everyday spaces haunting through his mise-en-scène and découpage. If we look at our lives from (literally) a different angle, there is definitely something macabre about it.

Jour de Fête

Jacques Tati’s debut feature, which focuses on how the Americans’ obsession with speed and efficiency, comes to haunt a postman – obviously played by Tati himself – on the same day a carnival is coming to town. Even Playtime is one of my favourite films ever, I shamefully admit this is only the second film I’ve seen from the man. There is an exhilaratingly fluent transitivity in how all the bits turn out. As Daney puts it, “Everything that is undertaken, planned, or scheduled works. And when there’s comedy, it’s precisely in the fact that it works.” Tati plays with the physical beings of every object and person within the frame, and there are no cuts to mask technical incompetencies; everything is so well thought out that the result can appear clumsy as intended.

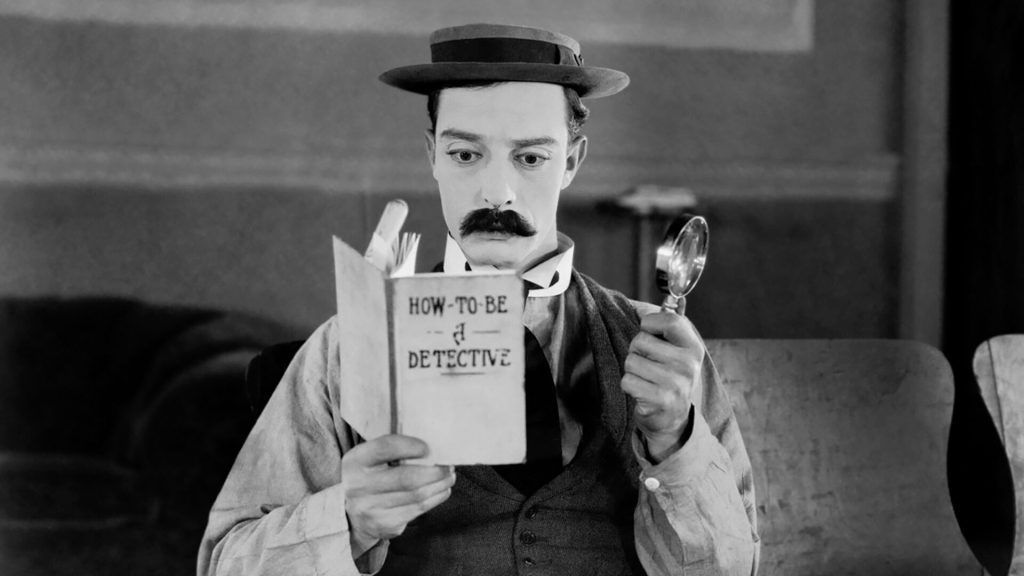

Sherlock Jr.

Speaking of, how can you not love Keaton when you love Tati? Despite seeing this close to the start of the month, certain stunt sequences that Keaton pulls off here remain ingrained in my mind. They have exceeded just a technical marvel -which is what I feel about The General sometimes- and ascended to something that spiritually speaks to me, and how I view cinema. The sequence where Keaton falls asleep and subsequently surrendipitously becomes involved in actions that take place in different settings, and the finale where he seeks instruction to kiss his girl, describes two foundamental ideas of cinema that I find extremely moving: one, it’s a way of seeing that can take us everywhere; and two, despite the ultimate limitations of representation, how it can capture and reflect real human emotions.

Leave a comment